Shannon Hayes, is co-owner of Sap-Bush Hollow Farm in West Volton, New York. She is the author of a number of books, and the host of the website theradicalhomemaker.net. We met the Ecological Farmers Association Conference in November 2017, at the Blue Mountain Inn where Shannon shared her thoughts and experience in this interview.

Shannon was a Speaker at the EFAO Conference

What made you decide to get into farming?

This is the way of life I’ve always known. I live just a few miles from where a grew up, the farm that I own is the one I grew up on, I grew up in the farm crisis and it was assumed that bright young people would leave the community and I became very keen- I was really keenly aware of that push when I was growing up- that there was a push to get out of town, to leave it all behind and I was actually a latchkey kid, and my parents held two full time jobs in order to keep the family farm and when I was a latchkey kid I was supported locally by the subsistence Appalachia farming culture that was there, and so I became very attached and even though I was academically promising, I had a hard time pushing that behind and I began to question why it was expected of me to leave- why that was the measure of success that I would leave this behind when I loved it so dearly. So that’s how I got started in it, I just couldn’t leave behind what I loved so much.

Can you describe a little bit the landscape of your farm?

My farm seize frost 11 months out of the year. It was considered non-viable in the nineteen seventies, the only advantage my farm and farming community had in the farm crisis was that we were considered non-viable before the crisis even hit, which meant we were considered non-viable when the push for industrialization happened. So it’s an area that did not see the industrialization of agriculture, the equipment just could not even make it to those hills in Hillside, they were too dangerous. So it’s very frosty, it’s very rocky, very hilly but fine for subsistence farming and to make a living on it had to be very creative because we couldn’t just raise a lot of product and sell a lot of product. We had to find ways to add value, we had to find ways to work with the landscape that was there for us.

How is it now? What has become the successful model with such a difficult landscape?

I have a hard time using the word model, because model would suggest that it could be replicated. And when anyone- it’s one thing to be inspired by somebody’s story, but your story could never replicate my story because you’ll just always be trying to live someone else’s story. What will make anyone else’s vision successful won’t ever be quite the same. Sorry could you ask me the question again? I just got hung up on the word model and then got distracted.

How have you turned those challenges into a positive?

Ok, so, my farm is a livestock grass fed, livestock farm, and what we have done is we start direct marketing the livestock to the broader community, and then my husband and I – as we came in to take over the family business, we realized we had to build on our unique strands. My father is an animal scientist but I’m not. And so that’s why I said there’s no such thing as a model. Each farm as the new generation comes on, has to be a negotiation between the land and the callings and the talents of the next generation. So I’m not the strongest person for animal husbandry, my husband and I are very good at being creative, we’re very good with engaging with people and we care a lot about people. And so for us to take the farm and move it forward we needed to build on that strand. So what we build is we bought a run down building in our hamlet and we created a farm to table cafe and espresso bar – which sounds silly, but we felt that my parents had built a very strong business, grass based farm business, and were very successful at selling those products and so to move into the next generation and capitalize on our skills – we happened to both be very very good at working together, and working in the kitchen, this is something we’ve always done. So those were skills where we knew we could make fast decisions, we could make economical decisions and we could really give something back to the community so our community has a farm to table cafe and espresso bar, it’s open only one day a week right now, in the summer it’s two days, because we run it just with our family, and it’s an opportunity to help our children develop their skills- I have one daughter who’s showing a lot of potential with livestock, and loves them very much, and this is helping her to build her people skills, and I have another daughter who’s very shy but who loves to be in the kitchen, and who loves food and flavour, and it’s building on her skills as well. So we created a place where our customers could relax when they come to get their meats, but where the community has a gathering space and we always threw very good parties, my husband and I, but we never actually liked to be the centre of the party, we just liked to create the space and that’s what we do now, you don’t spend a lot of time speaking to us but you get a sense of our hospitality when you come in. And I should say though, we still- our life is still very much about our home, because we still home school our children and we don’t go to jobs, the only reason why it’s only open one day a week is because we’re doing all the other things.

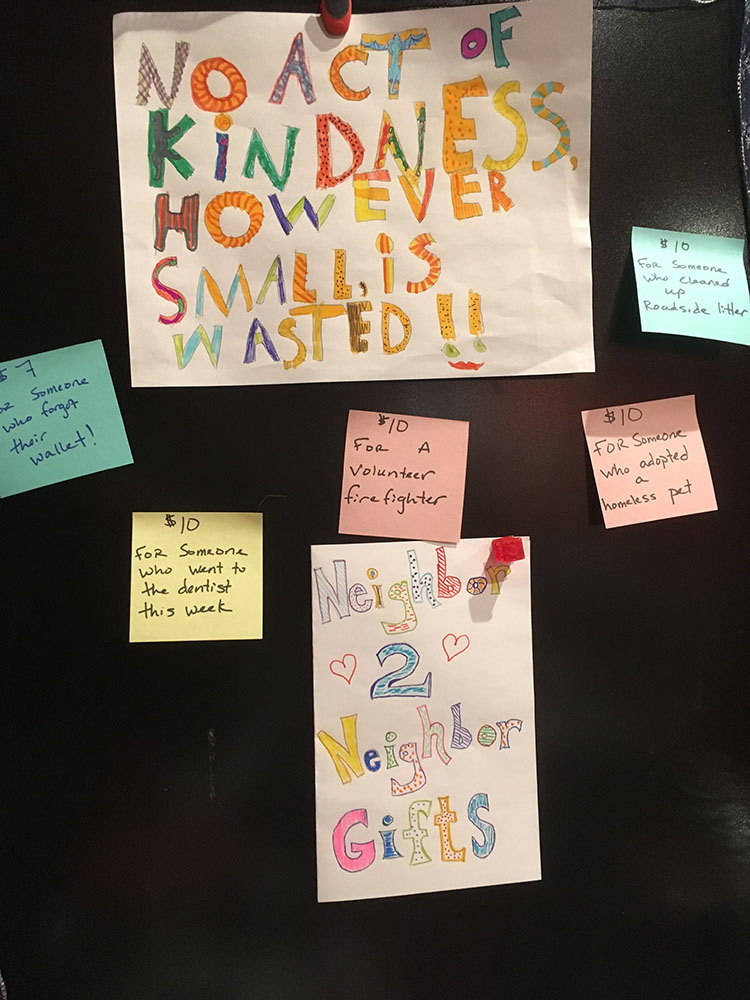

It’s very highly diversified, but it’s all one family business. So the business has pastured chicken, and pastured turkeys, and we do pastured eggs, and then we do grasped lambs and pastured pork and grassed. So all of that we sell retail out of the store, and we sell it at our farmer’s market as well. Then we built a system to try to enable all different income levels to participate, so if you go to the farmer’s market, it’s very- it’s our most expensive price is when we have driven it down to a farmer’s market and you wanna buy a single piece of meat for your weekend. Then we have wholesale sort of farm share program where people can buy wholesale chickens or they can buy a half pig, or they can buy a whole lamb. So that speaks to a different cross-section of the economy. And sometimes people move back and forth between simply being able to afford one piece of meat because they want a quick fancy week-end meal, and then people who are ready to make a bug commitment and buy a half pig or buy a whole lamb, and then within the cafe, we keep our meal, we do one farm to table meal each weekend. It changes every weekend based on what’s in season, and it always focused on what’s in season in our town so we work with another farm that grows the vegetables another farm that grows the fruit, and then we provide the meat.  And that meal is always changing, and that meal sells every weekend for 16.95$ which, for a farm to table meal, is very inexpensive, that includes your protein and includes your vegetables and it includes desert so it’s a full meal – a lot of people, when they come in, that’ll be their only meal for the day because we make sure that it’s very full, and then what happens is we have customers who are doing better economically, we have a board- a neighbour to neighbour board and then if they can pay extra, that money goes on the board and then we have other neighbours who don’t have as much money, and they can take a ticket off the board to bring their meal down. So we have about 30% of our customers who are in some kind of – they’re not at the standard normal income of the United States, but they find ways to participate- they either help or they get to take these stickers of the board or we work some other arrangement out so we’ve tried to build a system that everyone can participate in and that everyone feels free to participate in.

And that meal is always changing, and that meal sells every weekend for 16.95$ which, for a farm to table meal, is very inexpensive, that includes your protein and includes your vegetables and it includes desert so it’s a full meal – a lot of people, when they come in, that’ll be their only meal for the day because we make sure that it’s very full, and then what happens is we have customers who are doing better economically, we have a board- a neighbour to neighbour board and then if they can pay extra, that money goes on the board and then we have other neighbours who don’t have as much money, and they can take a ticket off the board to bring their meal down. So we have about 30% of our customers who are in some kind of – they’re not at the standard normal income of the United States, but they find ways to participate- they either help or they get to take these stickers of the board or we work some other arrangement out so we’ve tried to build a system that everyone can participate in and that everyone feels free to participate in.

What does sustainable living mean to you?

Are you coming to the talk tomorrow? So this is where I see the gaps right now, I’ve been in this movement for over twenty years and I have a PHD in sustainable agriculture and community development, I’m trained as a qualitative researcher and I guess you could say I’ve been a participant observer in this movement for close to thirty years, and then a full lifetime in another way, so I’ve been watching, and I saw the word sustainable bandied about in terms of environmentally friendly, and then I saw that term broadened to say environmentally friendly and a fair price to the farmer. Those are great things, but I don’t think we’ve gotten sustainable yet, because not only do we have to be environmentally friendly and has to pay a fair price to the farmer, but we have to work a fair amount of hours, we have to be able to disconnect and walk away and rest our bodies and rest our minds and I feel like that’s – that’s what I’ll be speaking about in depth tomorrow, that we can have a sustainable farm that our children will want to take over if we’re all working seventy hours a week we need to be able to walk away not only because we’re setting an example for our children that can be followed, because we can’t all be martyrs but also brain science is teaching us that if we want keep innovating and we wanna keep inventing, then working seventy hours a week is a sure way to fail. We will not replenish our spirits and our creative energies at those levels. So I’m very concerned about the ability for the movement not only to be appealing to the next generation, but also to continue to be inventive if we don’t start looking at reducing those numbers of hours that were working. So sustainability is good for the environment, sustainability is good for the body and mind- we can earn a fair wage, but it also allows us to get back to those for tenets: family and community, we need to be able to honour those things, we need to be able to rest, and we need to be able to be free in our minds to be creative and a half light of fancy because that’s where were going to see the next steps to take.

What’s an ideal home for you?

I’ve visited a lot of different homes, and to me, what’s ideal has nothing to do with income, and it has nothing to do with cleanliness, it has nothing to do with shininess. A home is a place that nurtures individuals to move forward and create a world that they can believe in. So we retreat into our homes for safety, for sustenance, and to rebuild our spirit, and to stimulate ourselves creatively. A home allows for those things to happen; there’s a balance of power and the ideas of the children are taken as seriously as the ideas of the adults and everyone is able to move forward with whatever their life calling is with the home as a support system to do that.

How a home and its occupancy sustained honourably?

Well what’s honourable is always going to be a matter of opinion, and my opinion is that there are four primary tenants that people can live by or that I can live by with my own family so I’ll speak for my own family. And that’s ecological sustainability, social justice, family and community. Ecological sustainability, it’s a do no harm kind of premise. Ideally our homes are not taxing the environment and ideally they are enabling us to live in a way that’ll help heal the earth and rebuild our communities and economy. When I say social justice, I say that means we’re trying to rebuild our communities and rebuild our quality of life without building on the back of others, without trying to take advantage of people who have to work for less than poverty wages and without assuming that somebody else is going to serve us at their expense so that we can benefit. And family and community, I believe those things need to be the centre of what our decisions are. I believe the home’s the centre economic unit for society, and therefore, when we engage in the broader economy, the home should not be sacrificed so we need to honour both family and community within our vocations.

How do you see that’s possible, is there a how to in here?

Well, I can tell you what I have seen possible from the path that I’ve walked, from the path that I’ve investigated. I don’t know that it’s the only way possible, but what I’ve been observing and what I’ve been writing about is how the use of the home can become a bridge between the extractive economy and the life serving economy that has now become a worldwide mission for many many people to rebuild. What the home can do is it enables us to – if we have enough domestic skills, wether it’s cooking for ourselves, growing our food, or basic self-reliance skills, those things enable us to pull away from an extractive economy, one that assumes that we will buy products where they can pollute the waters to make the product cheaply, or where people can be payed unfairly so that we can have products in abundance, and it lets us step back from that economy, that same extractive economy that expects us to work fifty to seventy hours a week when our bodies can’t sustain and our families can’t help so I see the home as the centre of production, where if we employ our domestic self-reliance skills, we reduce our reliance on an extractive economy and, by reducing our reliance, that home then enables to start bridging and building the new life-serving economy by creating businesses that let us keep our children at the fold, that let us pay people honourable wages, that let us engage with the environment in a way that nurtures it.

Would you like to comment, or is there anything you’d like to share with food paradox- you see anything you’d like to comment that’s a paradox of food?

We have a joke, Bob and I, we sell to a lot of people and we meet so many different people with what we do, and we have a joke where we’ll say “when someone walks up to us the first time, we look at the amount of expensive jewelry they’re wearing, and we can tell by the amount of expensive jewelry how willing they are to pay us a fair price for our product. And it’s inversely proportional. There used to be a push in the sustainable food movement to try for farmer to get into the most affluent markets and what I have learned is the affluence has nothing to do with the person’s willingness to look a farmer in the eye and pay them an honourable price for their food. It has nothing to do with it. There’s no correlation. Some people who are affluent understand hard work, but that doesn’t mean they’re going to pay it, therefore we have learned that some of our best customers are so economically disadvantaged but they work so hard for what they do that they never question what we need in order to live. And I guess, they are some who i’ve watched with their cellphones and their very expensive shirt and their very expensive jewelry look at me or look at the farmer who stands next to me at the farmer’s market and question us about why we should be paid what we’re paid, and I think that’s a paradox.